The Differences between Digital History and Digital Humanities

The revised & expanded version of this post published in Debates in Digital Humanities 2016 is now online.

For the last nine months I’ve spent much of my time exploring digital history. Part of becoming director of RRCHNM involved familiarizing myself with areas of work about which I had only passing knowledge despite almost twenty years of reading, teaching and creating digital history. Moreover, preparing for the Center’s pending 20th anniversary required looking back at more than 100 projects created in two decades of work. It was against this backdrop that I read the most recent outbreak of debate about digital humanities provoked by the special issue of differences, “In the Shadow of the Digital Humanities” (vol.25, no. 1, 2014), and Adam Kirsch’s article in the May 2014 issue of The New Republic, “Technology is Taking Over English Departments: The False Promise of Digital Humanities.” From that perspective, what is striking is the almost complete absences of digital history in those accounts. Matthew Kirschenbaum and others do make room for it by emphasizing the plurality of digital humanities and Lisa Rhody brings the key digital history text — Dan Cohen and Roy Rosenzweig’s Digital History — into the conversation – but ‘dh’ here is clearly standing in for digital literary studies.

My first reaction was a desire to highlight how the absence of digital history produces an impoverished vision of what digital humanities is. On reflection, in the US at this particular moment, fighting to get inside the big tent of digital humanities does not seem the most productive response. Instead, more can be gained from taking the debate as an opportunity to emphasize what makes digital history different from digital literary studies and ‘dh.’

Scholars exploring digital media and technology have gained much from emphasizing what they have in common, particularly in a context when such explorations enjoyed at best tenuous recognition within disciplinary settings. However, in recent years the consistent presence of digital sessions at the annual conferences of the AHA and OAH, as well as of smaller organizations such as the Southern Historical Association, the Urban History Association and the International Congress on Medieval Studies, testify to a growing recognition that digital media and technology are part of scholarly practice. But that recognition does not mean that most historians have explored what can be done with digital tools, are equipped to do so, or are even convinced that those tools have anything to offer their own research and teaching. Efforts to extend the conversation about digital history beyond the digitally fluent, those able to teach themselves, are not helped by calling our work “digital humanities”: rather, as Tom Scheinfeldt pointed out in his Day of DH 2014 post,

So what are the differences between digital history and ‘dh’/digital literary studies? In the current landscape in the US, broadly speaking, two stand out to me. First, the collection, presentation, and dissemination of material online is a more central part of digital history. Dan and Roy’s Digital History departs from the proliferating monographs and collections about digital humanities in being focused not on defining but on creating — or more precisely, on “gathering, preserving and presenting the past on the web.”  At RRCHNM, our mission is to use “digital media and technology to preserve and present history online, transform scholarship across the humanities, and advance historical education and understanding.” This focus has seen the Center create open access resources for K-12 & university teachers, build exhibits with library, archives and museums, collect born digital records, crowdsource transcription, and build open source software. As Tom Scheinfeldt has pointed out, these practices do not originate in humanities computing, the dominant origin story for digital humanities, but in oral history, folklore studies, radical history and public history. I’m not saying that the presentation of material online is not part of digital literary studies: electronic scholarly editions and manuscript collections such as The Shelley-Godwin Archive are longstanding parts of that field, but, as the current debate indicates, at present they are not its predominant focus.

At RRCHNM, our mission is to use “digital media and technology to preserve and present history online, transform scholarship across the humanities, and advance historical education and understanding.” This focus has seen the Center create open access resources for K-12 & university teachers, build exhibits with library, archives and museums, collect born digital records, crowdsource transcription, and build open source software. As Tom Scheinfeldt has pointed out, these practices do not originate in humanities computing, the dominant origin story for digital humanities, but in oral history, folklore studies, radical history and public history. I’m not saying that the presentation of material online is not part of digital literary studies: electronic scholarly editions and manuscript collections such as The Shelley-Godwin Archive are longstanding parts of that field, but, as the current debate indicates, at present they are not its predominant focus.

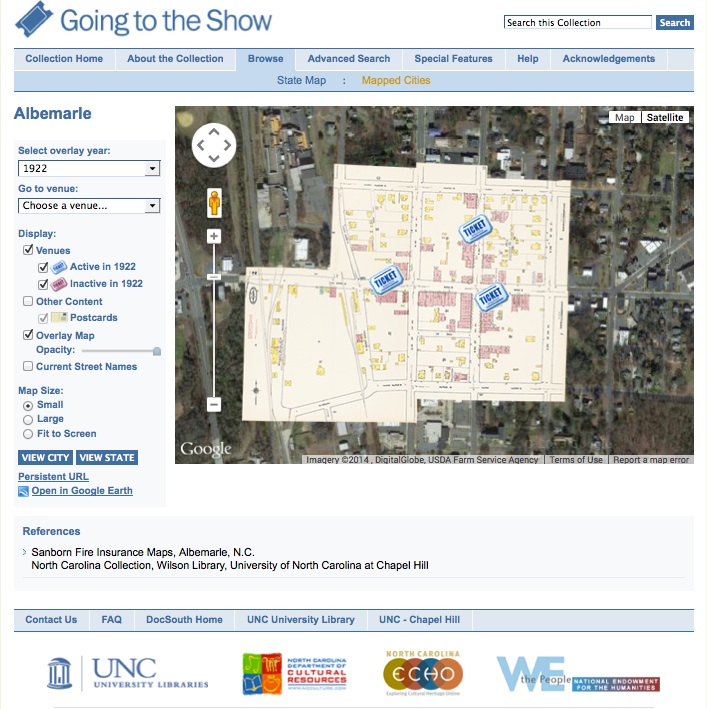

Second, in regards to digital analysis, digital history has seen more work in the area of digital mapping than has digital literary studies, where text mining and topic modeling are the predominant practices. The pioneering Valley of the Shadow project used mapping to understand and compare the two counties on which it focused. The first two winners of the AHA’s Roy Rosenzweig Prize for Innovation in Digital History were mapping projects: Digital Harlem: Everyday Life, 1915-1930 (which I created with collaborators at the University of Sydney) and Bobby Allen’s Going to the Show. Other prominent mapping projects include Visualizing Emancipation, ORBIS (The Stanford Geospatial Network Model of the Roman World), Mapping Texts, Slave Revolt in Jamaica, 1760-1761, The Roaring Twenties, PhilaPlace and Mapping the Republic of Letters.

Second, in regards to digital analysis, digital history has seen more work in the area of digital mapping than has digital literary studies, where text mining and topic modeling are the predominant practices. The pioneering Valley of the Shadow project used mapping to understand and compare the two counties on which it focused. The first two winners of the AHA’s Roy Rosenzweig Prize for Innovation in Digital History were mapping projects: Digital Harlem: Everyday Life, 1915-1930 (which I created with collaborators at the University of Sydney) and Bobby Allen’s Going to the Show. Other prominent mapping projects include Visualizing Emancipation, ORBIS (The Stanford Geospatial Network Model of the Roman World), Mapping Texts, Slave Revolt in Jamaica, 1760-1761, The Roaring Twenties, PhilaPlace and Mapping the Republic of Letters.

Again, that is not to say that mapping is not part of digital literary studies: Ryan Cordell’s Viral Texts is a noteworthy example. Nor is it to say that the textual analysis that predominates in digital literary studies has not been undertaken by historians. Dan Cohen and Fred Gibbs were among the first to experiment with data from Google books, and they went on to be part of the With Criminal Intent project datamining the Old Bailey trials. Rob Nelson, in Mining the Dispatch, used topic modeling to explore the Confederacy’s paper of record during the Civil War. The next issue of the Journal of American History will feature an article by Cameron Blevins that uses computational tools to analyze the view of the world offered by a late-nineteenth century Houston newspaper (an online essay describing his methods is already available).

Part of the explanation for why more historians have not undertaken text mining and topic modeling projects lies in the limited availability of machine readable texts: historians more often rely on unpublished sources than literary scholars, and on handwritten records that it is not yet possible to effectively use OCR to transform into machine readable text. And a wealth of printed, published texts have been digitized, only to be gated, available only to the small number of institutions that can afford the subscriptions, and even then without the API needed for computational analysis. (The recent announcement that the NAACP Papers had been digitized drew me to look again at the extensive archival collections in the hands of Proquest, in additional to their historical newspaper collections)

The opportunity for a deeper consideration of how historians have used digital media and technology, and of what makes them different from others in the digital humanities community as well as what they have in common, are part of what RRCHNM is aiming to provide in a forum and a resource on which we’re currently at work. The forum is our free 20th anniversary conference on November 14 and 15, 2014, for which you can register here. The resource is an online archive in which we are collecting the records that survive of the more than 100 projects produced in 20 years of work – from proposals to reports and as much in between as we can find. The site will provide material for the first day of the conference, devoted to hacking the Center’s history, and will be public, with an API. Our hope is that these efforts will, among other things, help in the project of re-engaging with disciplinary differences in digital humanities.

The opportunity for a deeper consideration of how historians have used digital media and technology, and of what makes them different from others in the digital humanities community as well as what they have in common, are part of what RRCHNM is aiming to provide in a forum and a resource on which we’re currently at work. The forum is our free 20th anniversary conference on November 14 and 15, 2014, for which you can register here. The resource is an online archive in which we are collecting the records that survive of the more than 100 projects produced in 20 years of work – from proposals to reports and as much in between as we can find. The site will provide material for the first day of the conference, devoted to hacking the Center’s history, and will be public, with an API. Our hope is that these efforts will, among other things, help in the project of re-engaging with disciplinary differences in digital humanities.

Follow-up post: Another Difference Between Digital History & Digital Humanities – Digital History and Teaching History

Great post! As the Rosenzweig/Cohen book gets older, I’ve been using two others that focus on history DH, Jack Dougherty and Kristen Nawrotzki, eds. Writing History in the Digital Age: a born-digital, open-review volume. online publication (2012) and Toni Weller, History in the Digital Age (2013). But most articles and DH books really do focus on literature studies.

Reblogged this on Christopher P. Sawula.

Reblogged this on Steven G. Anderson.