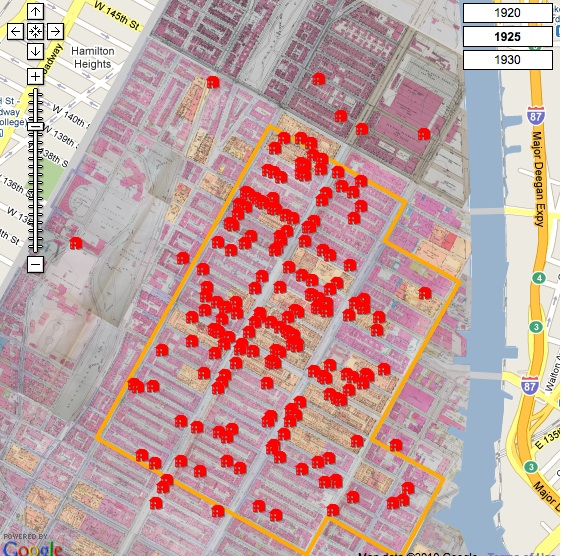

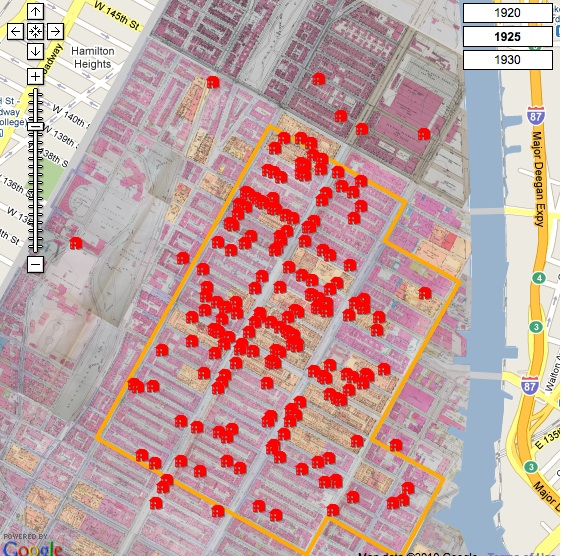

Beauty parlors were the most prevalent form of black business in Harlem in the 1920s and 1930s. When George Edmund Haynes, the black sociologist and founder of the Urban League, surveyed the neighborhood’s businesses in 1921 he found 103 hairdressers, compared to 63 tailors, pressers and cleaners and 51 barbers. Simm’s Blue Book, a directory of black businesses and professionals published in 1923, listed 161 beauty salons, more than any other enterprise. Combining that list with the businesses that advertised in Harlem’s newspapers, the map shows the location of 199 beauty parlors that operated in the 1920s. So many existed because it took relatively little capital to open a beauty parlor, particularly if you operated out of your home, as most women in Harlem did. Of the 103 hairdressers identified by Haynes in 1921, 46 operated out of stores and 57 from their homes. Beauty parlors also proliferated because the trade provided an alternative to domestic service, an occupation based in Harlem rather than in the homes of whites, which even if it still involved sweating and scrubbing was, in the words of an operator overheard by Federal Writers’ Project interviewer Vivian Morris in a salon in 1939,”cleaner and you don’t have no white folks goin’ around behind you trying to find a spec of dirt.”

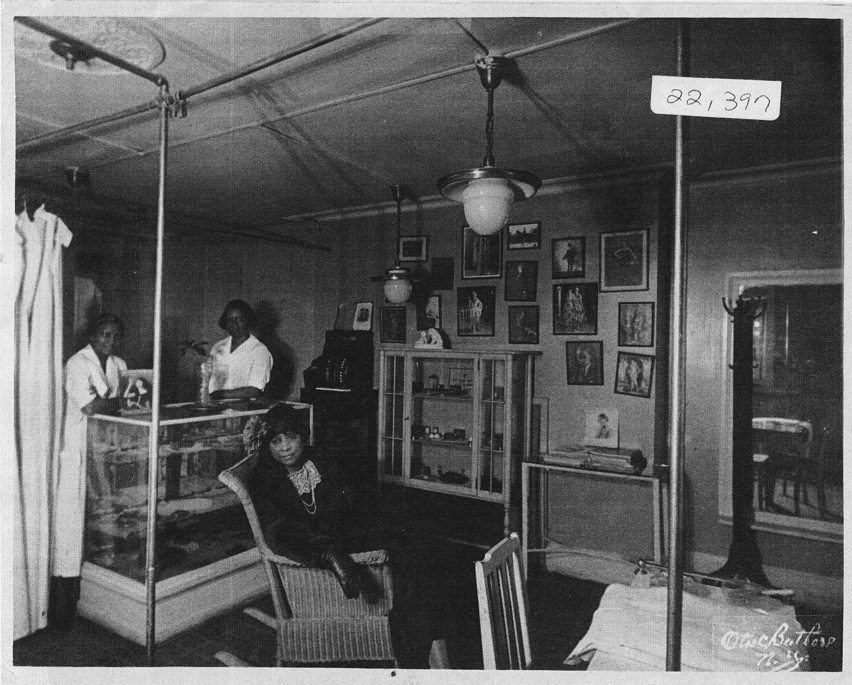

While most beauty salons were in homes, they were nonetheless a prominent presence along the streets occupied by the neighborhood’s businesses, particularly 7th Avenue (the photo on the left is of 2131 7th Avenue, near 125th St). Helen Bullitt Lowry, writing in the New York Times on August 21, 1921, associated beauty parlors with the more middle-class style of Seventh Avenue: On Lenox Avenue, “the proleteriat heart of the Black belt”, “the language is frank and from the shoulder. “Straightening combs fifteen cents.” But on Seventh Avenue, “the beauty parlors on the first floor hint more mysteriously. “Hair culture. The Poro System. Satisfaction guaranteed.” Groups of heads leaning out of any apartment house stone-cased windows demonstrate what it means to be permanently unkinked.” The map above, which draws on Simm’s Blue Book and later sources, shows only eight beauty parlors on Lenox Avenue, compared with 32 on 7th Avenue. By the 1930s, as the Depression brought an expansion in the beauty trade, which was perceived as “depression-proof,” 7th Avenue became dominated by beauty salons. In 1939, Vivian Morris, described a more elaborate geography that encompassed a cross-section of Harlem’s population: on the avenues between 135th and 110th Streets were beauty parlors that catered to the “average Harlemite,” particularly women employed as domestic servants; on 7th avenue between 135th and 138th Streets were the “Theatrical” parlors, which catered to men and women; while further north on 7th were the “elite” parlors whose clients came from the better residences of Sugar Hill, often by car; and finally, “hometown” shops filled the cross streets, bringing together operators and clients that hailed from the same parts of the South.

By far Harlem’s most elaborate beauty parlor was the Madam C. J. Walker Beauty Shoppe, at 110 West 136th Street, in the elaborate townhouse built by Walker in 1914, and occupied in the 1920s by her daughter A’Lelia, until it became the home of a government Health Centre in 1930. The building also housed a beauty school teaching the Walker System. At least five other beauty schools operated in Harlem, the largest being the Poro School, at 1997 7th Avenue, and the Apex School, on the corner of 7th Avenue and 135th Street, both of which taught nationally marketed systems that competed with the Walker system for dominance in Harlem and elsewhere in black America. In October 1927, for example, the Pittsburgh Courier‘s Harlem reporter claimed that Sarah Spencer-Washington, president of Apex Hair Company, had initiated a “Beauty War” by opening a string of new beauty parlors on 7th Avenue.

Much more than hairstyling took place in beauty parlors. They also served as centers of community life, places, as a writer in the Afro American put it in October 1926, where “one may learn the latest Harlem news, listen to the choicest bits of scandal, hear the private life of one’s neighbor’s discussed, and collect opinions of all and sundry on the events of the day.” Perhaps more unexpectedly, they were also “marts of exchange for everything salable from lingerie to tickets for dances, church socials or what have you.” Not all that business was legal, even in elite beauty parlors. While Vivian Morris was in “a swanky shop,” listening to customers discuss the international situation and the latest bestseller, a man entered, and went to the back of the shop, from where he sold “hot stuff,” stolen lingerie with ten dollar tags for three dollars.

At a “hometown” shop the illegal trade Morris witnessed was playing the numbers, with a runner arriving to collect bets from operators and customers. As more numbers betting moved to stores during the struggles between black and white bankers for control of the racket in Harlem, beauty parlors became centers for gambling. The New York Daily News in 1938 identified the Ritzy Beauty Salon at 351 Lenox Avenue, an Apex parlor based on the signs displayed in the window, as a numbers ‘headquarters.’

Harlem’s beauty parlors also contributed to life in the neighborhood in less direct ways. The career of A Philip Randolph, the socialist and founder of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, was supported by his wife Lucille Green Randolph, one of the first graduates of the Walker Beauty School in Harlem, who operated an exclusive beauty parlor on 135th Street from 1913 to 1927.

This is very interesting history to read about. I am a Licensed Filmmaker, Live near Hollywood ca. Thank You for Blogging this.

The modern incarnation of this is the hair braiding salon, of which there are an almost countless number in modern Harlem. They do braiding but also straightening and hair extensions, the latter two services being extremely popular, if the women on my morning commute are indicative.

My grandmother and her daughters frequently had their hair “done” at the Apex Beauty School in Harlem. When her granddaughters were preteens she took us A shampoo, dry, straightening comb , and followed by hot curls cost no more than $5.00 in early 1960’s.

We were always excited to go and mingle with the crowd of girls and women as we waited our turn to get a hair makeover.