When blacks moved to Harlem to live, they also looked to relocate and establish businesses. While the number of Harlem’s residences that were home to blacks steadily expanded, the neighborhood’s businesses remained largely in white hands through the 1920s. Thanks to the refusal of white banks to lend to blacks and white landlords to rent them space outside black neighborhoods, the scale and scope of black business remained limited, concentrated in the service sector and small in size. In the context of that discrimination, it is important to recognize business activity as an achievement not frame it as a failure. Barbers, the beauty trade, and undertakers were the engines of the black economy, benefitting from a lack of white competition, and proving more resilient in the face of the Depression than larger businesses.

Much of the evidence about black businesses comes from the pages of the New York Age (NYA). Unsurprisingly for a publication connected with Booker T. Washington, the newspaper was a committed booster of black business, publishing surveys as well as features on individual businesses, exhorting its readers to patronize those businesses, and criticizing the persistent failure of most residents to do so. (The race of the owners of businesses that appear in other sources are not always identified).

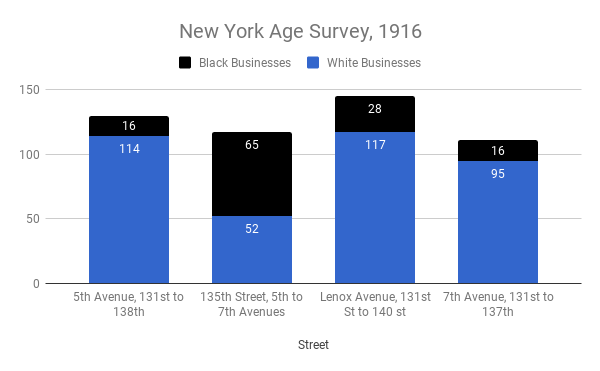

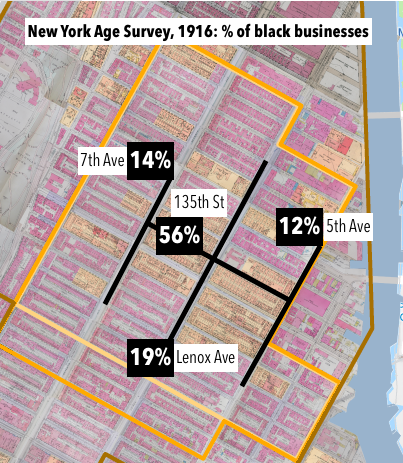

A survey by NYA reporters in 1916 found that whites owned 75 percent of the 503 businesses in the area where blacks lived, and employed only 150 blacks (1).

While the survey recorded the number of black business, it did not list their addresses, so we can’t map their location. It did specify the type of business, except on 7th Avenue. Of the 97 identified businesses, barbers made up the largest group, most on 135th St and Fifth Avenue, followed by grocers, restaurants, beauty salons, real estate offices, saloons and twenty-five other kinds of business.

As black settlement spread, the New York Age repeated its survey in 1921, finding an increased proportion of black businesses, but still white dominance (2).

Another key shift is evident in the 1921 survey: a spread of black business further along 7th and Lenox Avenues, beyond the solidly black areas of population, and a shift west in the orientation of black Harlem towards 7th Avenue, also evident in the omission of 5th Avenue and 135th Street from Lenox Avenue to 5th Avenue from the 1921 survey.

Real Estate offices were the largest category of the 168 businesses in the 1921 survey, followed by barbers, beauty salons, tailors and restaurants. On this occasion, the paper offered brief vignettes of businesses. For example:

Another of the older business organizations on Seventh Avenue is the Harlem Music Shop. This business was started five years ago in a small store on 137th street. It was the first Negro music shop opened in the city. The company moved into larger quarters at 2365 Seventh avenue about three years ago, and is now the largest colored music store in the city. Besides phonograph records and piano music rolls, this company is the agent for a large piano player firm in the city. The proprietor of the store is James H. Tetley (3).

Simms Blue Book and National Negro Business and Professional Directory published in 1923 provided the addresses of 425 of Harlem’s black businesses and professional offices. Although that number is far greater than reported by the NYA, it is not evidence of further expansion in black business activity so much as a picture of what the newspaper’s investigations missed.

Simms Blue Book produces a very different map of black business than the NYA surveys, showing businesses and offices located in homes on Harlem’s cross streets not the retail spaces on the avenues that the NYA reporters visited. Most of the largest category of business in Simms, beauty parlors, operated in homes on Harlem’s cross streets not in retail spaces. The doctor’s offices that are the second largest category in Simms were likewise were most often found on residential streets. Conversely, some businesses operating on the avenues identified by the NYA are missing from Simms. The different pictures of black business offer by the NYA and Simms also show gender in a different light. Women operated Harlem’s beauty parlors; when those businesses are included, women appear as a far more significant force in the neighborhood’s business activity. (Missing from all these counts are day nurseries, women offering child care in their homes. Advertisements allow them to be mapped, but do not offer evidence of the race of their operators).

However, Simms Blue Book is not a comprehensive survey of neighborhood businesses, including more than 250 fewer businesses than sociologist George Haynes counted in his study of Harlem in 1921(which provides no addresses to map), and only 29 types of business compared to the 50 types that Haynes identified . Haynes’ numbers show a similar concentration of activity to Simms Blue Book while showing significantly more tailors, dressmakers and restaurants.

In explaining why they did not patronize black businesses, Harlem residents claimed white businesses carried more stock, provided better service and charged lower prices, and that white professionals had greater skill (4). And in many cases, thanks to the refusal of whites to provide blacks with capital to stock their businesses and access to training, they were correct. The NYA accepted such complaints in regards to an older generation of businessmen, “the old time, slow, sleepy negro business man,” with “his gloomy, half-lit, half-stocked place of business,” but pronounced the 1920s a new era, in which “keener men” would win black patronage (5). The experiences of one firm celebrated by the paper suggested otherwise. Bell and Delaney, a menswear store in a new building on the corner of 135th Street and Seventh Avenue, managed by William K. Bell and backed by Hubert Delaney, an assistant U.S. District Attorney, and his sister Sarah, a high school teacher, had the fittings and fashions of “a regular Fifth Avenue shop,” not to mention the imprimatur of its middle-class owners. When the business celebrated its fifth anniversary in 1930, the Amsterdam News lauded it a success (6). Bell wrote to the paper to qualify that achievement:

It has not been an easy task to go these five years. . . . Our people, at first, are slow in patronizing their own businesses, because a great many of them think that their own just cannot give them the same values that other people give for the same prices. But just stick long enough with fair business methods, and gain their confidence, and many in our group will walk any number of blocks to spend one nickel with you (7).

More often than not, however, residents chose to walk right on by black businesses, and into the stores of their white competitors. They would not support the race at the expense of their ability to consume equally, as Americans. Alongside all that happened in Harlem to give blacks a new consciousness of what they could achieve, shopping offered a contrary picture of limits that remained.

It was against this backdrop that the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA), the black nationalist organization founded by Marcus Garvey, established the African Communities’ League in 1918 and the Negro Factories Corporation in 1920 as the business side of the organization, to show that blacks could compete with whites and make them self-reliant. In the early 1920s, the UNIA operated a laundry, a tailor and dressmaker, 3 grocery stores, 2 restaurants and a printing plant. By 1922, most were out of business.

Notes

(1) NYA, March 9, 1916, 1; March 16, 1916, 1; March 23, 1916, 1; March 30, 1916, 1; April 6, 1916, 1; April 13, 1916, 1.

(2) NYA, February 12, 1921, 1, 4; February 19, 1921, 1; March 5, 1921, 1; March 12, 1921, 1.

(3) NYA, February 19, 1921, 1.

(4) NYA, April 13, 1916, 1, 2; NYA, September 30, 1922, 1; NYA, June 23, 1923, 1; AN, February 16, 1927, 4; The World, August 19, 1928, 8E; AN, March 25, 1925, 16.

(5) NYA, July 17, 1920, 1.

(6) AN, July 23, 1930, 2.

(7) AN, July 30, 1930, 20.

More Reading:

Stephen Robertson, Shane White, and Stephen Garton, “Harlem in Black and White: Mapping Race and Place in the 1920s,” Journal of Urban History 39, 5 (September 2013): 864-880 [Open access version]

1 thought on “Black Businesses in 1920s Harlem”