By 1930, there were more than 24,000 school-age black children in Harlem (1). Five public elementary served the black community in the 1920s, with two new junior high schools built in the 1920s, PS 139 (boys), which opened in 1924, and PS 136 (girls), which opened in 1925. The one secondary school located in black Harlem in the 1920s was an industrial school for boys on 138th Street, which occupied the building that until 1914 had been PS 100. (Harlem was also home to three Catholic Schools)

New York law prohibited segregation, and in the early 1920s all of Harlem’s schools contained both black and white students. However, residential patterns created de facto segregation; as the neighborhood’s population became almost entirely black, so did its schools (2). (Note the black population boundaries on the map). The industrial high school was the exception; in 1930, three-quarters of its students came from white neighborhoods across the river in the Bronx.

While the pupils in Harlem’s schools became almost entirely black, the teachers remained overwhelming white. In 1920, PS 89, for example, had only twelve black teachers among its fifty-nine staff (3). In 1928, only one hundred of the five hundred teachers in Harlem’s eight public schools were black (4). But that proportion of black teachers was higher than in other northern cities (5).

The presence of dwindling numbers of white students and persistently high proportions of white teachers apparently led to almost no racial conflict within Harlem schools, at least as reported by the black press. An incident at PS 5 in 1928 in which a white teacher threatened to flog a black boy like they did in the South was reported as the first instance of children being molested by white teachers in the 1920s (6). An investigation in 1935 did report “a great deal of turnover in the white personnel of these schools” and “a disproportionate number of older white teachers,” who “are naturally impatient and unsympathetic towards the children” (7).

New York City’s [white] school administrators adjusted the curriculum in Harlem’s schools in response to the arrival of black students, adding more vocational training in place of higher level academic classes. For boys that meant classes in operating low-skilled machinery and in service industry etiquette, and for girls in dressmaking and domestic work. Schools relied on intelligence testing to identify which students should be sent to those classes, and also used them to classify students transferring from southern schools, who were generally at least a year behind local children. The focus on vocational classes enjoyed wide support among Harlem’s black leaders and in the black press (8). Controversy did flare in 1926 over claims that the principal of PS 136, the girls’ junior high school, was steering her pupils toward vocational programs rather than college preparatory courses (9).

As early as 1921, Harlem’s schools were so congested that they had to run double sessions, meaning that students were only able to attend for part of the day. That year there were 26 double sessions at PS 90, 24 at PS 5, 16 at PS 89, 8 at PS 119, 7 at PS 68 (10). The construction of the junior high schools brought some relief to the overcrowded elementary schools, but Harlem schools remained at or over capacity into the 1930s as the Board of Education failed to add schools to keep pace with the growing population. The Depression brought cuts to spending on the schools, exacerbating the pressure on school facilities. By 1935, conditions had deteriorated to a level that horrified investigators:

On the day that one or our investigators visited this building, the first thing that attracted his attention in the principal’s office was a pile of old shoes strung across the floor and a pile of old clothes stacked in one corner. The principal’s office was equipped with an old dilapidated desk and two chairs, one of which was broken… The classrooms are dark and stuffy; the blackboards are old and defective, and the wooden floors are dirty and offensive… Moreover, the school has no gymnasium or library and generally lacks in the educational equipment which is deemed necessary in modern schools of its grade (The Complete Report of Mayor LaGuardia’s Commission on the Harlem Riot of March 19, 1935, 78-80).

Continuing on to high school required leaving Harlem. The closest high school to Harlem was Wadleigh High School, an option for the neighborhood’s girls. Few black girls attended Wadleigh before the 1930s; they made up 25% of the students in 1937 (11). The nearest boys high schools were De Witt Clinton High School on West 59th Street (renamed Haarn High School in 1927) and George Washington High School on West 192nd Street. A study in 1926 found 507 black children in New York City high schools (12).

By 1927, three of Harlem’s public schools, P.S. 89, 90, and 136, were also home to public evening vocational schools. One evening school catered to men, at PS 89; in 1927, it offered ten classes with over 400 students (13). For men, the city’s evening classes provided a path to white-collar work; by contrast, they equipped women for industrial work. In 1928, over one thousand women attended the evening school at PS 136 for classes in dressmaking, sewing, embroidery, lamp shade making, novelty work, cooking, artificial flower making, millinery, interior decorating and painting lamp shades and silks (14).

PS 5

- Built: 1894-1899

- Capacity: 2799 students (1934) / Enrollment: 2996 (1913)

- Teachers: 76 (1937)

PS 68

- Built: 1875-1906

- Capacity: 1056 students (1934) / Enrollment: 1561 (1913); “nearly 1500” (1931)

- Teachers: 40 (1931); 48 (1937)

- No outdoor playground; 128th St closed to traffic from 12-1pm

PS 89

- Built: 1889-1895

- Capacity: 1875 pupils (1934) / Enrollment: 1841 (1913)

- Teachers: 62 (1934)

- Evening vocational school (men)

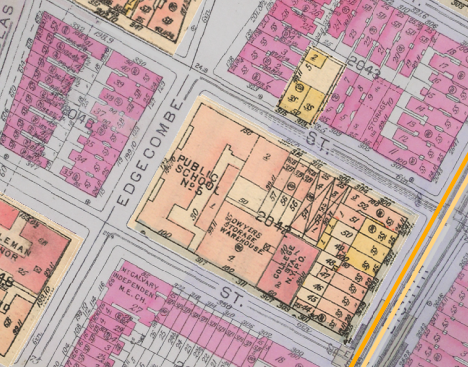

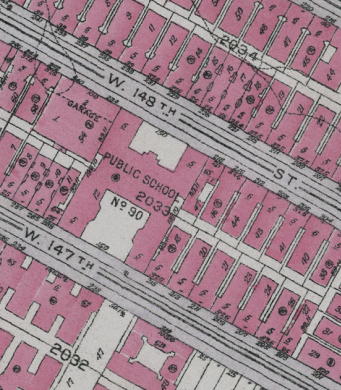

PS 90

- Built: 1907

- Capacity: 2547 students (1934): Enrollment: 2666 (1913)

- Teachers: 78 (1929); 70 (1934)

- Evening vocational school (women)

PS 119

- Built: 1900

- Capacity: 1800 (1925); 2500 students (1934) / Enrollment: 2080 (1913); 2540 (1920)

- Teachers: 60 (1937)

PS 136

- Built: 1925

- Capacity: 1886 students (1934) / Enrollment: 1774 students (1926)

- Teachers: 100 (1937)

- Evening vocational school #157 (women)

PS 139

- Built: 1924

- Capacity: 1482 students (1934)

- Teachers: 66 (1937)

There is a large playground outside and the entire ground floor is a gymnasium gymnasium with showers and a lunch kitchen. The second floor has the offices of the principal and his assistant; kindergarten, kindergarten, class rooms and an auditorium auditorium seating 550 people with a motion picture booth and a stage. The third floor has the medical department department with its waiting room, teacher’s rest room, library, open air room and gymnasium for the juniors. On the fourth floor is the drawing room, music room and science room. The fifth floor is given to manual training Shop. A and B, with class rooms and office of the industrial department (NYA, August 30, 1924, 1).

Information on dates of construction and capacity from Maps and charts prepared by the Slum Clearance Committee of New York, 1933-34, page 96:

Notes

(1) Owen Lovejoy, The Negro Children of New York City (Children’s Aid Society, 1932), 11.

(2) Frances Blascoer, Colored School Children in New York (New York: Public Education Association of the City of New York, 1915), 11-12; NYA, March 12, 1921, 1; Floyd Snelson, “The Negro in New York Public Schools,” Federal Writers Project, October 3, 1937.

(3) NYA, January 17, 1920, 1.

(4) World, July 1, 1928, 7.

(5) Thomas Harbison, “Part of the Problem or Part of the Solution? Harlem’s Public Schools, 1914-1954,” PhD dissertation, CUNY, 2011.

(6) Afro American, June 23, 1928, 5.

(7) The Complete Report of Mayor LaGuardia’s Commission on the Harlem Riot of March 19, 1935, 81-82.

(8) Harbison, chapter 1.

(9) NYA May 29, 1926, 1, 2; June 5, 1926, 1, 2.

(10) NYA, March 12, 1921, 1.

(11) Floyd Snelson, “The Negro in New York Public Schools,” Federal Writers Project, October 3, 1937.

(12) AN, 2/2/1927, 15.

(13) NYA, 10/22/1927, 3.

(14) AN, 1/25/1928, 7.

My Mom, Gussie Fischsohn Jacobs, taught 1st grade at PS 33 in Harlem from 1927 through 1937. She believed that the sound teaching/learning of the basic fundamentals would give her students the knowledge that would enable them to move forward. I certainly hope she was correct; she must have poured a tremendous amount of thought, energy, time and perseverance into her teaching.

After I was born, my parents moved to the Bronx, where my mom taught first graders for another 25 years. Parents requested her for their children. Many student teachers observed her classroom. She was inspirational.

.