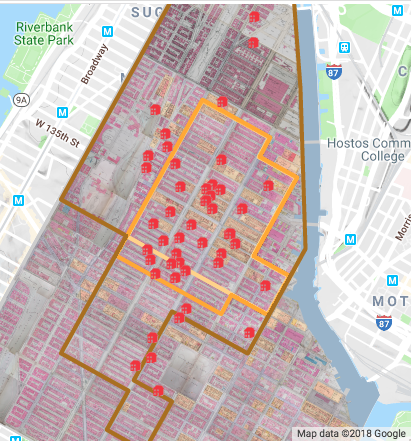

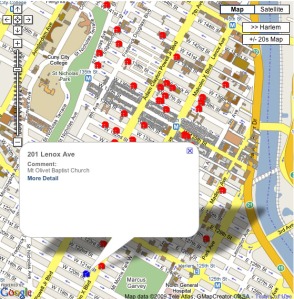

Churches were the most prominent black places and institutions in Harlem. They made a powerful impression on visitors to the neighborhood, such as the (white?) journalist who wrote in The Independent in 1921 that “In the main, [Harlem] is impressive. Especially the churches.” This map shows 52 black church buildings located in the neighborhood. They were home to a variety of Christian denominations: Baptist; African Methodist Episcopal; Protestant Episcopal; Presbyterian; Congregationalist; Catholic; 7th Day Adventist; African Orthodox, Holiness; and Apostolic.

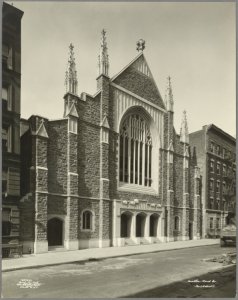

A number were elaborate, grand complexes, which coupled houses of worship that seated over a thousand, with community houses, incorporating gymnasiums, reading rooms, recreation rooms and offices. The buildings reflect the broad role Harlem’s churches played in community life: they organized athletic clubs (particularly basketball teams), classes ranging from vocational training to art, choirs and musical groups, and social clubs. It was such activities that James Weldon Johnson had in mind when he wrote in Black Manhattan (1930) that a Harlem church is “much more besides a place of worship. It is a social center, it is a club, it is an arena or the exercise of one’s capabilities and powers, a world in which one may achieve self-realization and preferment (165).”

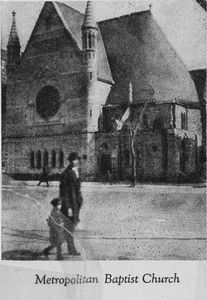

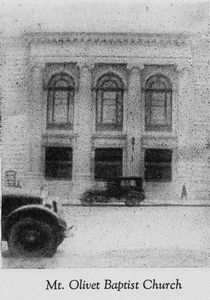

Fourteen of the largest churches were purchased by black congregations moving uptown from white congregations (Christian and Jewish), whose members had left Harlem. These included:

|

|

|

|

|

The other congregations that had taken over church buildings in Harlem by 1930 were: Mother Zion AME Church (136th St); Grace Congregational Church (139th St); Emanuel AME Church (119th St); Salem Methodist Church (129th St); St John AME Church (128th St); Mt Calvary United Methodist Church (Edgecombe Ave); Little Mount Zion AME Church (140th St); Transfiguration Lutheran Church (126th St); Williams Institutional CME Church (130th St), St Martins Episcopal Church (Lenox Ave) and Ephesesus 7th-Day Adventist Church (Lenox Ave).

Not all the church buildings in Harlem passed into the hands of black churches. The Catholic Church retained its presence in Harlem, preaching to congregations increasingly made up of blacks.

Nine other relocating black congregations built their own grand churches, including St Philip’s Protestant Episcopal Church on West 134th Street (the wealthiest church in Harlem), the Abyssinian Baptist Church on West 138th St, which seated 3000, and St Mark’s Methodist Church, with seating for 2000.

|

|

|

|

|

|

The other churches built by blacks were: Mother Zion AME Church (137th St); St James Presbyterian Church (137th St); Salem United Methodist (133rd); Rush Memorial (138th St); the Metropolitan Baptist Tabernacle (138th St); and Shiloh Baptist (7th Ave). Smaller churches converted residences or theatres, such as Metropolitan AME Church (134th St) and Union Baptist Church (145th St).

Mother Zion AME Church pursued both strategies, first taking over a church on West 136th St, and then building its own, more elaborate building behind that structure, facing West 137th Street, with a community house and gymnasium.

|

|

|

|

|

As the example of Mother Zion suggests, setting up in Harlem was often not the final move a congregation made. It was common to relocate within the neighborhood, seeking more space as membership grew. Thus while on first glance the map suggests Harlem’s churches were spread throughout the neighborhood, by the late 1920s, most of the major houses of worship were located on or near 7th Avenue, or further west. That was where the churches built by white congregations were located. Only below 125th Street, where the black population did not predominate until 1930, were there major church buildings on Lenox Avenue and further east.

The location of Harlem’s church buildings had an impact on the spaces around them. As Theophilus Lewis noted in his column in The Amsterdam News on January 22, 1930, “As most of the churches, and the biggest ones, are either on [7th] Avenue or only a few steps away, the thoroughfare is also the main artery of the town’s religious life (9).” The concentration of structures concentrated Harlem’s churchgoers, giving the street a religious character – at least on Sunday mornings. As Lewis went on to note, twelve hours earlier, on Saturday evenings, 7th Avenue was a “hub of amusement,” filled with “throngs out for hours of joy” in the very forms of leisure that many Harlem clergy denounced as the greatest obstacles to religious practice.

Church buildings were not the only locations in which Harlemites worshiped. Missing from this map are the churches that operated in storefronts and residences, which far outnumbered those housed in church buildings. Writing in Opportunity magazine in 1926, Ira Reid reported finding 140 churches in 150 blocks in Harlem; two thirds were located in former storefronts, on the first floor of private dwellings, or in the back room of a flat (274). A portion of those churches were what James Weldon Johnson, in his Black Manhattan, described as “ephemeral and nomadic,…here today and gone somewhere else or gone entirely tomorrow (163-4).” Reid experienced that turnover: returning six weeks after he made his list, seven of the churches could no longer be found (275). Both this transience, and the location of these churches within structures designed for other purposes, meant that they had less of an impact on the streetscape of Harlem than the church buildings that appear on this map. Rather than marking out distinct spaces within the neighborhood, storefront churches contributed to the fluidity of commercial spaces: a store could be not only a place of commerce; it could also be a place of worship, or a front for the sale of illegal liquor — a speakeasy — or for the numbers racket.

See also: “Catholics in 1920s Harlem”

REFERENCES:

“Churches,” Box 2, Reel 2, Writers Program Collection (WPA) (Schomburg Centre for Research in Black Culture)

David Dunlap, From Abyssinian to Zion: A Guide to Manhattan’s Houses of Worship (New York, 2004)

Cynthia Hickman, Harlem Churches at the End of the Twentieth Century (New York, 2001).

3 thoughts on “Churches”