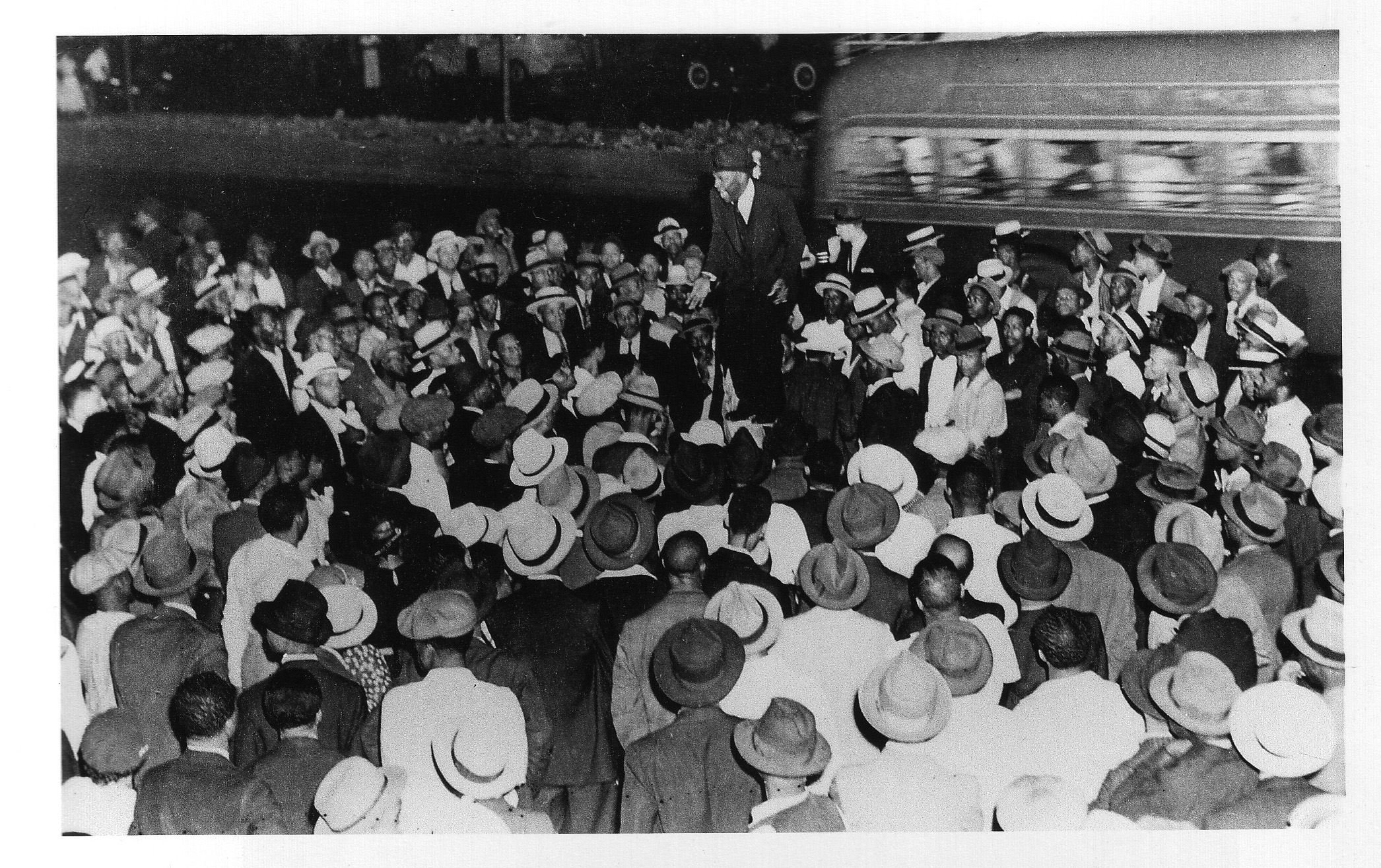

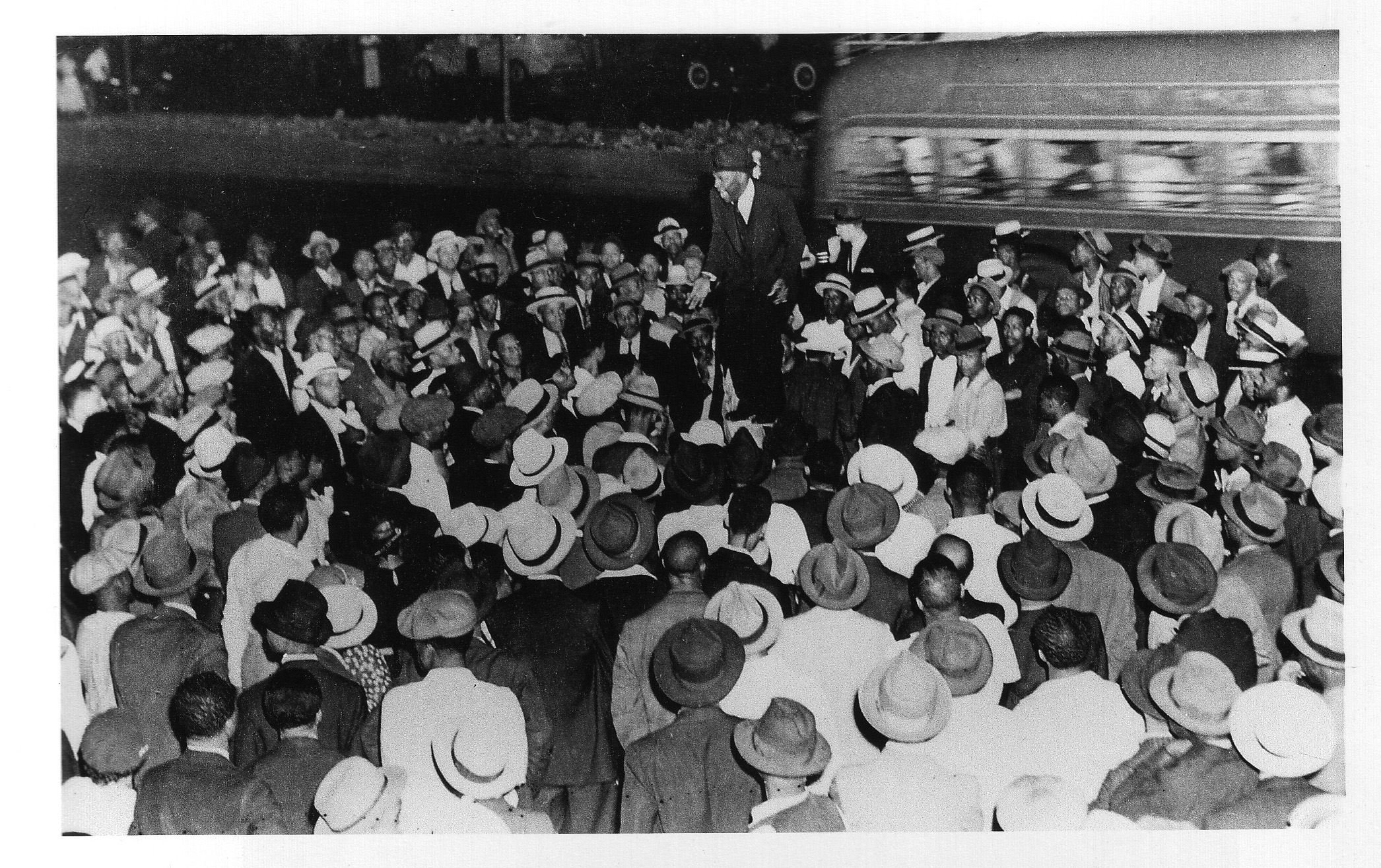

Soapbox or street corner speakers were a feature of everyday life in Harlem from World War One to the 1960s. Each year, the appearance of speakers was heralded as a sign of spring, and they were particularly prevalent through the summer months, when the heat led residents of Harlem to spend most of their leisure outdoors. The first speakers were political orators, with West Indian members of the Socialist Party such as A. Philip Randolph and Richard Moore most prominent. They set up at 135th Street and Lenox Avenue, which offered a wide sidewalk and a steady stream of passers-by coming to the surrounding stores or entering and exiting the subway station. Crowds numbering in the hundreds stopped to listen. Marcus Garvey made his debut in Harlem at that corner in 1916, and he and members of his organization, the UNIA, regularly spoke on the neighborhood’s streets throughout the 1920s.

By 1921, socialists could be found at other corners along Lenox Avenue, and on Sunday evenings, at 135th Street and Seventh Avenue. Later in the 1920s, speakers also set up along Seventh Avenue, as it rather than Lenox became Harlem’s main street. In the 1930s, speakers could be found on both avenues as far south as 115th Street and as far north as 144th Street.

Hubert Harrison, Harlem’s most famous street speaker, began as a socialist, but became famous for his lectures discussing “philosophy, psychology, economics, literature, astronomy or the drama.” [1] By the mid-1920s, he drew crowds numbering in the thousands. A reporter exiting the Lafayette Theater on to Seventh Avenue one evening in 1926 encountered “one of the biggest street corner audiences that we have ever met,” an audience whose “faces were fixed on a black man who stood on a ladder platform, with his back to the avenue and the passing buses and his face to the audience who blocked the spacious sidewalk.” [2] It was Harrison, speaking on the theory of evolution. Harrison died in 1927; no other orator demonstrated his learning or achieved his stature. For listeners, even lesser street speakers represented an alternative to churches and middle-class organizations, a source of more radical ideas, less constrained by institutional authority. On the street, speakers were accessible, available for sampling by residents out for a stroll or doing their shopping, who might not otherwise have had the time to seek out orators. Middle-class critics complained of the ignorance of some speakers, of the misinformation they spread, of the racial hatred they aroused.

In the later half of the 1920s, political orators were outnumbered by speakers selling medicine. Many were East Africans, or West Indians posing as Africans, who attracted crowds with elaborate costumes and performances. Journalist Lester Walton, who campaigned against such “quacks,” described them in terms that expressed his frustration at the credulity of his black neighbors, but also conveyed some sense of what drew in passers-by:

They lend a theatrical touch to their manipulations by dressing in gaudy costumes of supposedly foreign make, and attractively decorate the platform with multi-colored ribbons, bunting and the like. Attention of pedestrians is first gained by performing a feat of magic, such as turning wine into water. Next rheumatism or some other chronic disease is dwelt on and a cure, whose reliability is proclaimed beyond any question, is offered for what is represented to be an amazingly small price.” [3]

Not all those offering something for sale were black. According to Walton, some of the medicine vendors were whites posing as American Indians. Whites were also among those selling things other than medicine. Edgar Grey reported that Gypsies returned to Harlem’s street corners between 1922 and 1924, establishing ‘shops of astrology,’ while another journalist encountered “a dingy Czechoslovak,” “a provincially dressed peasant [with] a beautifully colored parrot on his shoulder,” and “innumerable Gypsies,” all offering to tell his fortune or reveal a winning number.[4] The first speaker Walton heard in 1928 turned out to be selling a dream book. Others collected funds for business enterprises: Hubert Julian, the black aviator, could be found in May 1925 at 140th Street and Seventh Avenue selling razors donated to him to pay for the plane he hoped to fly across the Atlantic.

In the 1930s, political speakers returned to prominence, and appeared in new locations, particularly on 125th Street, in the vicinity of Harlem’s major white-owned businesses. From there, they played a significant role in mobilizing support for campaigns to force white retailers to hire black staff, increasingly speaking on behalf of organizations and at regular times and places. Some, however, also drew on the appeals employed by medicine sellers. Sufi Abdul Hamid, who arrived in Harlem in 1932, fresh from a successful campaign to win jobs for blacks in Chicago, rallied residents dressed in a white turban, green shirt, black riding boots and a black crimson-lined cape.

[1] Pittsburgh Courier, December 31, 1927

[2] New York News, 1926, cited in Irma Watkins-Owens, Blood Relations, 94

[3] “Street Speaker Heralds Spring in Harlem,” World, March 23, 1928, 17M

[4] Amsterdam News, March 30, 1927, 16; Amsterdam News, August 19, 1931, 9

Just read the article on Soapbox. My cousin Arthur Reed was a soap box speaker and the first to introduce Black dolls. I remember Adam Clayton Powell picketing Blumstein’s Department store to hire black staff. As a teenager, I could not try on hats, shoes or any article there.

Two years ago I wrote an article entitled “The Harlem I Knew.”

I now live in St. Augustine, Florida and both Blacks and whites can hardly believe the stories I tell about discrimination in New Yosrk in the 30′ and 40’s.

Blessings,

Dr Dee

Thank you for this article, especially since the photo by the Smith brothers shows my husband ‘s and thousands of Blacks mentor, Mr. Carlos Alexander Cooks, then president of the Advance Division of the Universal Negro Improvement Association. Cooks formed the charter after Garvey’s deportation, but with his permission as he told Cooks to, ” keep on, keeping on”. My husband, now deceased joined him in 1962 as a member of the African Nationalist Pioneer Movement. They held massive Garvey Day parades, socials and built a building called the Marcus Garvey Memorial building that was a magnificent structure. It would be later razed and replaced bythe city for a hi rise. Cooks held the tenets of Garveyism, published The Street Speaker Magazine, and had a vibrant African Legion. Malcolm X was inspired by him and peppered his speeches with Cookisms. When he left the Nation of Islam he formed Muslim Mosque Inc. whose tenet was a muslim faith but African nationalist economic, social and fraternal institution.