Until the mid-1920s, Harlem’s children went to summer camps organized by the city’s Fresh Air Fund (FAF) and other groups inspired by its model. Established in 1877, FAF focused initially on rural home stays, but in the early twentieth century began to run summer camps, initially for groups that “it is not wise to place with private hosts.” Black children were one such group; in the 1910s FAF organized camps with black organizations, including the Urban League (1). Some black children were placed with other groups, such as the Christian Herald, which had been operating Mont Lawn Camp at Nyack since 1894. The YWCA also established a camp for girls in 1920, in Palisades Interstate Park. Frustration with the difficulty in placing black children in these camps, which had limited the number of campers from Harlem to 1100 or less than 5% of the the estimated population of 5-14 year olds in 1926, led to the formation of a Harlem Committee of the Fresh Air Fund in 1927 to expand opportunities for black children (2).

Black groups in Harlem began to establish their own summer camps. In 1927, St. Phillips P.E. Church opened Camp Guilford Bower outside New Paltz in 1927, followed in 1928 by the North Harlem Community Council, who purchased a camp at Livingston Manor, in 1929 by the Harlem Fresh Air Fund, who purchased Camp James Farely near Poughkeepsie, and by the New York City Mission Society who opened Camp Minisink near Port Jervis in 1930. Access to these sites, and annual fundraising drives to send children to camps, promoted by the Amsterdam News in particular, saw more than 3000 children attending summer camps by the early 1930s (3). Even as the Depression took hold and donations fell, Harlem organizations continued to raise funds to send children to camp – although St. Phillips P.E. Church did have to sell its camp in 1936, to the Children’s Aid Society.

Like vacation playgrounds, summer camps provided a place for children when school was closed and Harlem offered little other than the streets. But their proponents argued camps offered the additional benefit of getting children out of the city entirely. The Fresh Air Fund made the case that summer camps kept children “away from city streets; from the torrid heat of New York summers; from ill-health” (4). The YWCA likewise emphasized the health benefits of time at camp, away from the “tension” and “daily humdrum” of the city, as a means to store up energy for next winter’s work (5). Historian Brian McCammack has recently pointed out the additional dimensions of the temporary, restorative escape from the city for black children; that black summer camps served as “potent racial idylls: their remote locations, separate from whites, laid the foundations for race pride and dignity in ways that were difficult if not impossible in the city [due to] environmental inequalities, segregation and racist treatment (6).”

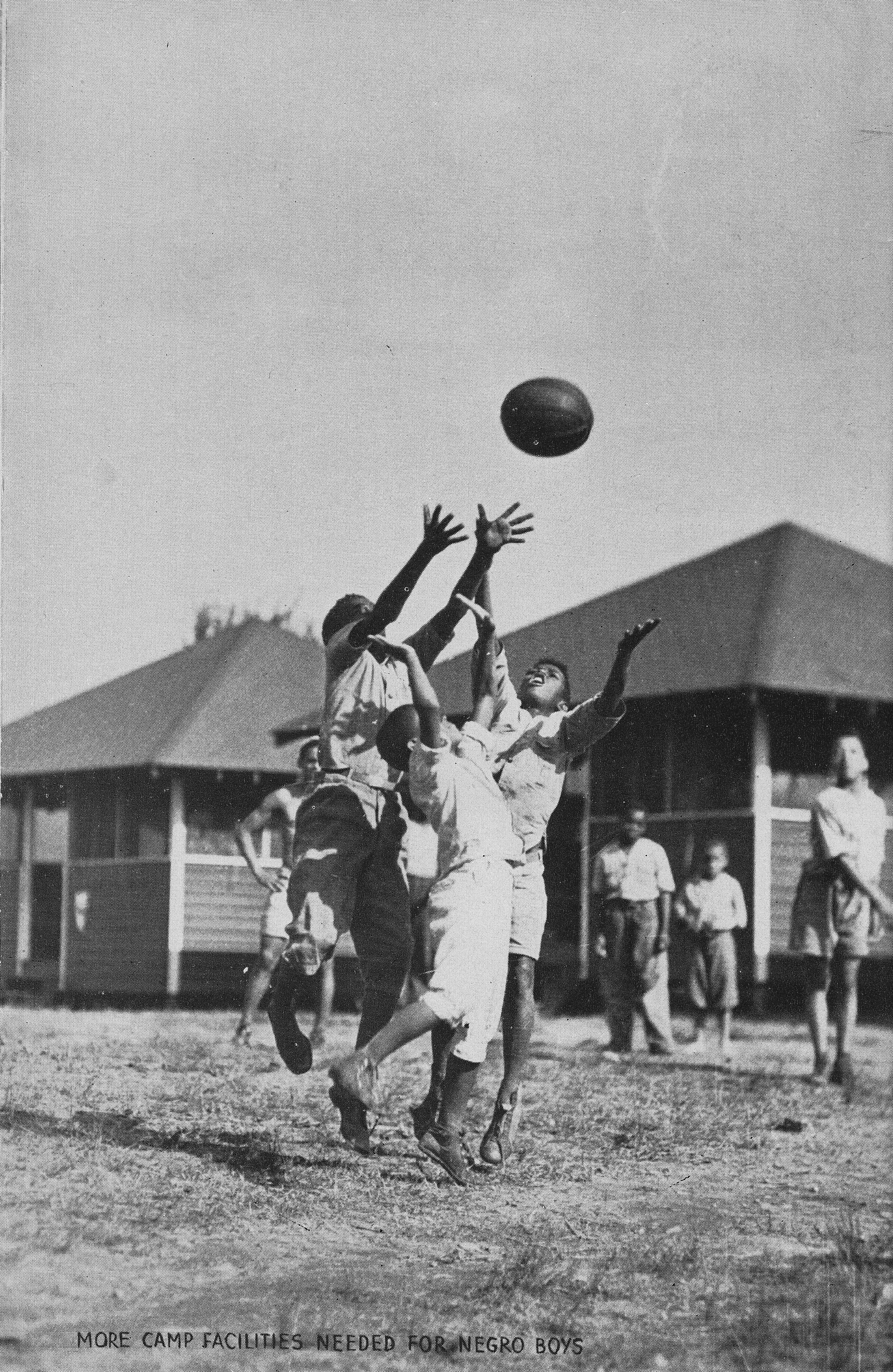

Boating, swimming and hiking had the most prominent place in reports of camp activity. Although accounts of camps never failed to mention the beauty of their natural environment, campers spent much of their time around the camp buildings rather than in nature. Sports was central; most camps had a gymnasium and facilities for basketball , tennis and baseball. As with vacation playgrounds, camps competed against each other in sports, including swimming (7). Girls camps also had handicrafts and other hobbies. Music and dances also featured among the activities.

Camps, like playgrounds, centered on supervised or organized play. The camp counsellor’s role was very much like that of the playground supervisor, and was performed by educated members of the professional class and church groups, who received specific training. In 1935, the YWCA’s Fern Rock Camp was staffed by a director, Mrs Mabelle White Williams, a physician, a dietician, two handicraft counsellors, a vocal and instrumental music counselor, four swimming counselors (one a man), and a coordinating counselor (8). Camp life followed a routine, including chores and meals in orderly dining halls, and sought to instill healthy habits to take back to the city. While camp publicity emphasized chaperoned activities ranging from calisthenic exercises to group hikes, swimming lessons and refereed sports games, being at camp offered similar respite from this discipline to that found in playgrounds (9). One girl camper described a typical day at Camp Minisink as beginning with exercises at 6.30am, followed by chores, then hobby or rest period and swimming period. Dinner was at 6.30pm, after which the candy store opened (10).

Adults, as well as children, left Harlem for camps in the summer. Each year the 369th Regiment paraded from the Armory on 143rd Street to the train depot at East 125th Street, and then travelled to Camp Smith. Established in 1882 as a training site for National Guard regiments, the camp was named for Governor Alfred Smith in 1919. During the regiment’s time in camp in 1927, they paraded daily, spent four days on the rifle range, and then focused on battle practice in the second week. In the evening there were parades and band concerts. Just over 1000 men made the trip in 1930.The camp was opened to visitors one day. On their return, the Regiment again paraded through Harlem. (11)

Camp Guilford Bower, outside New Paltz, New York, about 85 miles from NYC.

Sponsored by St. Phillips P.E. Church from 1927 until sold to the Children’ Aid Society in May 1936 (who renamed it Camp Wallkill). The sale resulted from the church’s inability to put in the money needed to operate the camp during the Depression (12).

The camp comprised a farm of 314 acres that maintained 40 cattle year round. It was originally planned for boys and girls not qualifying for Fresh Air camps and was interdenominational. In 1930, the camp opened on July 3, with 144 children aged from 8 to 18 years, and a staff of 35, and expected to care for at least 500 children before closing for the season in September 4. Children remained at the camp for two weeks or longer.

Camp James Farley, 5 miles east of Poughkeepsie

Purchased by the Harlem Children’s Fresh Air Fund in July 1929, from former NY State Assemblyman E A Johnson (the first African American member of the NY State Assembly), who sold the property at a discounted price (13). An 86 acre farm, with a large 13-room house. When the farm was purchased, 50 acres was ready for cultivation, with 125 fruit trees already planted. Plans for development included damming a stream to create a swimming pool, converting buildings to create dormitories, a mess hall and gymnasium, and building tennis and baseball grounds. Named for James Farley of the State Athletic Commission, a supporter of the Fresh Air Fund (14).

In 1930, the camp opened on July 21, for 50 girls aged 7 to 12 years, who remained for two weeks, looked after by a staff of trained camp counsellors and a graduate nurse. They stayed in a 13-room house at the camp (15).

Livingston Manor, Sullivan County, NY.

North Harlem Community Council Camp purchased the camp at Livingston Manor in 1928 (16). An area of 86 acres, it included nine cottages, a 19 room house and a gymnasium (17).

In 1930, the camp opened on July 15, with around 100 children at a time staying for two weeks until September 1, with a staff on 11 camp leaders. In 1929, 5 groups of 250 children each stayed at the camp for two weeks (18)

Camp Minisink, Port Jervis, NY.

Operated by the New York City Mission Society, Camp Minisink opened in 1930. The camp covered 300 acres and included two lakes used for boating and swimming. The camp hosted approximately 500 children for two week vacations by 1935, with girls and boys attending in separate groups. (). Camp counsellors were drawn from church groups in Harlem; the camp director in 1931, for example, was Daniel Taylor of Mother A.M.E Zion Church on West 136th Street (19).

Fern Rock Camp, Lake Tiorati, Palisades Interstate Park. 45 miles from Harlem.

Established by the YWCA in 1920, to serve girls aged 7 to 17 years. At first, the site had no hot water or electricity. In 1923, the camp was described as made up of “rustic sleeping huts [with open sides] and a dining and recreation hut with an open fireplace (20). The camp expanded in 1928 with enclosed cabins, an infirmary, a living room with fireplace, and a kitchen. Activities included swimming, boating, hikes, camp fires. (21)

Mont Lawn Camp, Nyack, NY.

Sponsored by the Christian Herald (419 4th Ave). 60 boys from Harlem went in 1929, and again in 1930, when it opened on June 26 (22)

Notes

(1) Julia Guarneri, “Changing Strategies for Child Welfare, Enduring Beliefs about Childhood: The Fresh Air Fund, 1877–1926,” The Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era 11, 1 (2012); NYA, June 28, 1919, 2.

(2) AN, June 22, 1927, 5.

(3) AN, June 2, 1934, 2

(4) AN, June 22, 1927, 5.

(5) AN, July 6, 1935, 9; NYA, 6 June 1923, 8.

(6) Brian McCammack, Landscapes of Hope: Nature and the Great Migration in Chicago (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2017), 100.

(7) AN, August 30, 1933, 14.

(8) AN, July 6, 1935, 9.

(9) Guarneri, 51-53.

(10) AN, June 22, 1935, 8.

(11) AN, August 22, 1927, 3; AN, September 24, 1930, 3.

(12) AN, May 23, 1936, 5.

(13) AN, February 1,1928, 6.

(14) AN, July 31, 1929, 3.

(15) AN, July 9, 1930, 5.

(16) AN, July 29, 1931, 20.

(17) AN, 10 July, 1929, 14.

(18) AN, April 23, 1930, 4.

(19) AN, June 22, 1935, 8; AN, September 21, 1935, 3; NYA, 4 July, 1931, 7.

(20) NYA, January 29, 1927, 2; AN, June 20, 1923, 7.

(21) Judith Weisenfeld, African American Women and Christian Activism: New York’s Black YWCA, 1905-1945 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1998),186-87; NYA, June 23, 1923, 8.

(22) AN, April 23, 1930, 4.

My aunt was a camp counsellor at Camp Minisink in 1958 and I have been reading the diary I have of hers that she kept in her stay. She was from the UK and was just visiting the USA to be at her camp. She later returned to the States in 1962 and then worked at Inwood House in New York, carrying on with her connections to Camp Minisink. It was very interesting to read your article as I am trying to find out more about the context of my aunt’s life in the USA.